It was well below freezing as my sister pulled up to the south Kaibab trailhead. I opened the passenger door and stepped out with my daypack, adjusting my headlamp before stuffing my hands into a pair of North Face gloves. I was accompanied by my friend Lee, who had previously joined me on climbs up several of Colorado’s more difficult 14ers (those mountains that stand over 14,000 feet above sea level). I took the last few bites of an energy bar and set my Garmin watch to hiking mode. It was 3:58 in the morning.

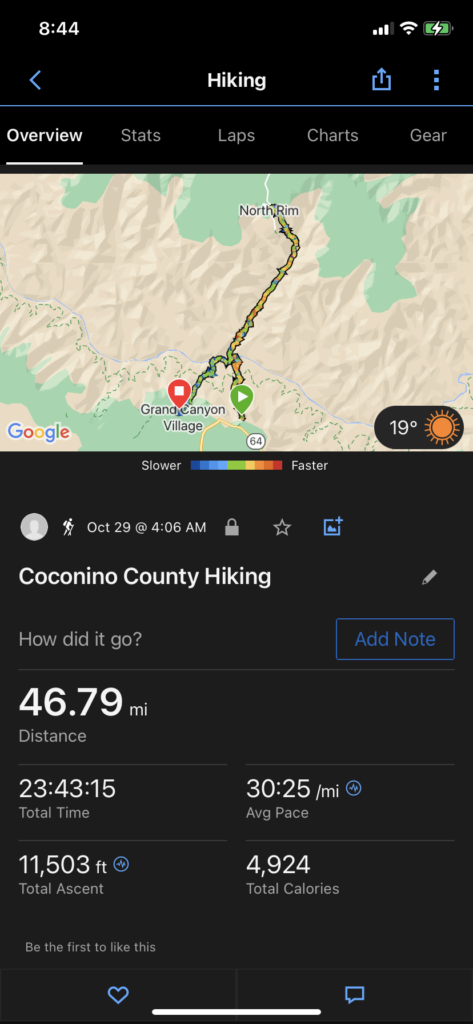

Lee and I had both backpacked this infamous hike through the Grand Canyon long before we met. But backpacking the canyon allowed us three days to meander down the south rim, up to the north rim, and then back to the south rim. Hiking rim-to-rim-to-rim (r2r2r), taking south Kaibab trail out and Bright Angel trail on the return, adds up to about 47 miles and involves nearly 12,000 feet of vertical gain and loss. Our mission on this day was simple: hike to the north rim and back in less than 24 hours. We certainly weren’t going for a speed record, but finishing in 24 hours would allow for very few breaks. Our stops for water would be quick and we’d eat on the go. If time allowed, we would take a short break once we reached the north rim.

It was late October and the forecast for the day was dreamy and clear. The highs at the canyon floor were about 75 degrees, with lows at the north rim around 25 degrees. My sister, Sherie, had flown from Florida to support my latest adventure challenge, something I was inspired to take on after reading Michael Easter’s Comfort Crisis. I’d spent the last few years pushing my mental and physical boundaries in the mountains, but it had been 13 years since I really tested myself.

In 2010, I bicycled the transamerica trail, mostly alone, and self-supported. It took me 75 days to finish the 4,200 mile cross-country trek from Virginia to Oregon, and I returned a completely transformed person. From there, my hunger for adventure was ignited, alongside an intrinsic desire to persistently test myself, to find out what I was made of.

BUT…all my adventures since had been things I was always relatively sure I could complete. The transam was the last time I took on something without feeling fully confident I would finish. Frankly, I hadn’t given this much thought until I read about the misogi challenge in Easter’s book.

The concept of the misogi is simple. It’s something that should be really, really hard. It should be uncomfortable. It should suck. Annual misogi challenges are encouraged to test and prepare yourself to take on the next 364 days.

The first rule of misogi is that it should be so challenging that if all variables worked in your favor, you might have a 50% chance of completing. The second rule is that you can’t die.

Given that the most miles I’d previously covered in a day was about 18, the 47 miles of r2r2r seemed like misogi territory. Also, I’d never had to deal with the sleep deprivation that I knew would be an inevitable part of this challenge. With that, I called Lee, explained what a misogi was, and asked if he was down. Without pause, he replied, “when we doing this thing?”

I checked my pack one last time, which was full of the essentials to make sure I didn’t break misogi rule #2: extra headlamp, phone battery, first aid kit, Garmin GPS beacon, about three thousand calories of food, a water filter, and an emergency bivy. I was already wearing all my layers, which I would peel off as the temperatures rose.

I tossed on my pack and hugged my sister. “I’ll see you in 24 hours,” I said. “Hopefully,” I added, with a laugh.

With that, Lee and I began making our way down to the canyon floor under a glorious full moon. The descent into the canyon was fast and easy. We reached the Colorado river within a couple of hours, just as the sun began to rise. From there, we had about 9 miles of a gentle incline before the steeper ascent up the north rim began. Everything felt great, my body felt strong, and our pace was solid.

We got water at the Manzanita rest stop and began the steeper part of the trek. The climb was steady. We reached the north rim around 3pm, took a 10-minute break, and then headed back down.

The sun was setting as we got back to the Manzanita rest area, where we both filled our bottles and slapped some mole skin on our feet. The days were short and we both donned our headlamps as we resumed the hike. It was around this time that I first noticed my feet feeling tired and sore. My glutes and hip flexors were also beginning to talk to me, but I resisted taking the ibuprofen that was stashed in my first aid kit. I wanted to feel the discomfort. This was what I came for.

We stopped at phantom ranch, the rustic oasis nestled at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. It was midnight, so we had about four hours to get back up the south rim. I laid down on a picnic table to stretch my back and hips. By this time, my feet were really starting to hurt. I took off my shoes and was relieved to see I didn’t have any blisters forming. After nearly 100,000 steps, my feet were just tired. Lee and I ate some peanut M&Ms and then headed out for the last leg of the hike.

The fatigue and soreness made the hike back up the south rim far more difficult than the north rim ascent. As soon as we crossed the bridge that spans the Colorado river, I started experiencing excruciating, shooting pain in my hips. The first few steps up a rocky part of the trail made me gasp and I was suddenly flooded with doubt. What if I couldn’t make it back up? Would every step for the next four hours hurt this bad? Would it get worse? I wanted discomfort and boy was I getting it. The pain was one thing, but it was like my muscles suddenly weren’t working as they were supposed to. My steps up were awkward and weird and my quads felt completely fried.

I wasn’t going to be able to just gut this one out. I needed a new strategy.

I told Lee I wanted to stop for a minute to try stretching my angry muscles. I remembered I had a tiny tube of muscle rub in my pack. A moment later, I found myself standing in the middle of the trail with my pants around my ankles as I rubbed balm into my hips and glutes. I tuned into my body to try to understand what it was telling me and what I needed to do to adapt. I pulled my pants up, slipped on my pack, and began moving back up the trail. Everything from the waist down hurt, but I paid close attention to how each movement felt. I realized that my quads were toast, which was causing exaggerated movement in my hips with every step upward – and this movement was quickly causing my hips to burn up. I decided to try altering my movements slightly to force my glutes to take more of the load, because they still felt strong. I adjusted to this new movement pattern within a few minutes and the shooting pain stopped, so we continued on.

With about 3 miles to go, I began to feel dizzy and punch drunk. I’d tried to stay on top of my hydration and nutrition, but my body was telling me it needed more fuel. The thought of taking another bite of anything sugary or processed made my stomach turn, but I choked down a handful of gummy bears and felt instantly better. It was 2:30 in the morning and I was starting to feel confident that we were going hit our 24-hour goal.

As I closed in on the last half mile, I took my phone off airplane mode and texted my sister. She was at the south rim and had spotted our headlamps. “I see you!” she texted. I looked up and saw a tiny light moving back and forth at to the top of the rim, as Sherie waved her cell phone at me. About 15 minutes later, I was greeted at the south rim by my sister. I looked down at my watch. Our total time was 23 hours, 47 minutes. We’d made it with 13 minutes to spare.

Here’s the big thing I took away from this particular challenge.

I realized that I was nowhere near the edges of what was physically possible. Lee and I mused about this over dinner a few days later. Both of us agreed that we most certainly could have kept going. We wondered how much longer it would have taken for us to really get to the point of tapping out. How much more could we have given before the exhaustion and pain became too much? 12 hours? Another 24?

These questions just led to bigger, more profound questions: Where else in my life had I been selling myself short? When had I not taken something on because I didn’t believe I could finish? Where else had I been leaving so much on the table? These are some of the very empowering questions you ask yourself after a misogi.

And here’s the thing. It’s not actually about whether you complete the challenge as prescribed. What matters is that you try. Really try. Give it all you have and empty the tank in a genuine effort to find out just how much is in there to begin with. Had I finished in 25 hours, I still would have had these questions because of data that challenged my previously held beliefs.

Whether you test yourself once a year or more regularly, it’s important to do things that help you discover what you’re made of. Even better, when you know you have a big challenge coming up, you’ve got something tangible to train for. You have metrics you can track. You can create a system to hold yourself accountable because you know that challenge is fast approaching. It’s there, nipping at your heels every time you think about skipping a training session or binging on garbage. Big challenges are powerful accountability partners.

The benefits of hard physical challenges are undeniable. When was the last time you truly tested yourself? When did you last prove something to yourself? What challenges have you got planned to find out what’s in your tank?